Adolf Behne, Die Wiederkehr der Kunst [The Return of Art], Leipzig: Kurt Wolff Verlag, 1919.

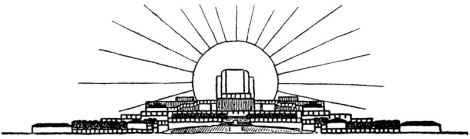

Adolf Behne’s The Return of Art is an extended and rhapsodically-argued treatise offering an expressionist perspective on the regeneration of art. Taking Paul Scheerbart and Bruno Taut as especially important points of reference, and enthusiastically embracing their conception of glass architecture, Behne’s work provides a philosophical and political complement to Scheerbart’s and Taut’s literary and artistic visions.

Clearly echoing their most extreme encomiums of the miraculous social and spiritual effects of building with glass, he writes: “Glass architecture ushers in the spiritual revolution of the European, making a restricted, vain animal of habits into an awakened, bright, fine, and delicate man” (66). Behne considers glass, as artistic and architectural material, to already be dematerialized, hence latently spiritualized: “No material overcomes matter so fully as glass…. It reflects the sky and sun, it is like lighted water and it possesses a richness of possibilities of color, form, character, which truly cannot be exhausted and which can be indifferent to no man” (67).

As these passages about glass already indicate, however, Behne’s text is in no way a work of conventional art criticism and is only to a limited extent a treatise on aesthetics. Rather, taking art as a key index of the spiritual situation of contemporary Europe after the debacle of the First World War, Behne offers a thoroughgoing critique of European modernity, identifying as its component elements the separation of art from everyday experience, the dominance of technology and the production of functional objects, the capitalistic and bureaucratic division of labor, class hierarchy and the oppression of the masses, and the individualistic and nihilistic anarchy of spiritual life. The task of his book is nothing less than to project the overcoming of European humanity: “We must overcome the European. This challenge is the alpha and omega. As Europeans we can go no farther. Only where the European ceases does the world become beautiful” (64). Recurring to the motif of glass architecture, it is precisely glass, as a medium of construction, that may transform and symbolize a renewed European man: “Glass will transform him. Glass is clear and angular, but in its hidden richness it is mild and delicate. The new European will also become thus: clearly determined yet completely tranquil” (69).

Behne can encompass all this under the aegis of the question of art (recall his title: The Return of Art) by defining art, dogmatically and metaphysically, as nothing other than the expression of the Absolute. The experience of art, therefore, is that of spiritual transcendence, both of material existence and of the individual self. Moreover, as something absolute, true art brooks no division, of genre, medium, or historical difference. “Art,” he writes, “is always the One” (8). Contrary to humanist and secular conceptions of art, he explains that art’s absolute nature reveals itself in taking distance from the world of the human in favor of superhuman, spiritual contents: “In the true artwork the human is no plus, but rather a minus… The more that man in his finitude disappears, the more pure and consummate will be the artwork” (34).

Any particular realization of art may be more or less in communication with art’s absolute nature. European art, however, after its Gothic flourishing, has been characterized by a deleterious subdivision into separate arts and genres, a classicistic restriction of its expressive means, a subordination of the artist’s spiritual role to commerce and individualistic prestige, and a loss of connection with the popular masses. The capacity of European art to express the spiritual strivings of the people—as Behne argues it once did in the Gothic epoch and still does in other parts of the world such as India—has all but completely disintegrated. Above all, for Behne, this is true of architecture, which he understands to be, in its essence, the most integral and spiritually unifying manifestation of art, but which, in modern times, has become little more than a servant of capitalism, technology, and the state.

Indeed, architecture derives, in Behne’s conception, from the very nature of the world as structured and formed, which in turn makes it the ultimate expression of creation itself. Architecture, as a manifestation of the world itself, englobes the other arts: “The world is first of all building—not painting or sculpture. Building is the elemental art. The works of the other arts must be housed, and building creates around them this house” (43). “The becoming of the world,” he continues, “is a building, and through human beings filled with love for the world mankind builds in concert with the self-completing form of the world” (44). In turn, architecture can become “a work that is the embodied will of human being towards love of the world” (56).

Behne introduces a schematic typology that places architecture at the acme of a spiritual -artistic hierarchy, stretching from the “I” outwards towards the cosmos:

“The bow of art spans between lyric and architecture, with epic resting in the middle of its course.

Architecture is religious art, lyric is erotic art, epic is worldly art.

The nourishment of architecture is the cosmos; of the lyric, the ego; of the epic mankind” (16-17).

Behne’s point, however, is not so much to distinguish these types of art as to argue that any authentic expression of art requires elements of each—and also, negatively, to diagnose the shortcomings of the modern European conception of art, which reinforces these typological differences instead of striving towards their synthesis in a higher unity.

Modern art created within the broad current of “cubism” and “expressionism,” may be, Behne suggests, pointing the way beyond the decay represented by neo-classicism, naturalism, and impressionism:

“In fact, painting today gives us a greater hope that the goal, unity, may be achieved, in the art actually called to leadership: architecture. There thus also goes out the call to all young architects to do their part, so that architecture can get out of its current dead-end path” (24).

Somewhat more improbably, but perhaps implicitly referencing modernist forms of primativism, Behne also argues that the new tendencies in painting should allow a reconciliation of art with the people, reforging a link once manifest in the medieval society in Europe and still intact in other parts of the world, but that was shattered by the bourgeois individualism of the 19th and early 20th century.

Now, with cubism and expressionism, which breaks with tradition not only aesthetically, but also socially, “a new folk art” (101) may begin.

Not only through his affirmation of emerging avant-garde forms, however, does Behne assert an aesthetic populism and counter the restrictive artistic conventions that constituted the measure of high art in his day. In a more surprising turn of argument, he also defends, even affirms: kitsch. “That which today’s society calls art,” Behne writes, “is nothing but a sum of negations…. If we must, however, tie the actualization of the ideal to something positive, then this can only be done insofar as we say yes to kitsch” (92-93). He continues: “We should not be frightened by so-called kitsch. Kitsch is the production of a mass, upon which the pressure of cultivated society and its art weighs. As soon as this pressure disappears, the production of the mass will receive air and light, purity and courage, and will then progress to that which we have habitually called folk art” (93).

One implication of Behne’s metaphysical conception of art is his consequent anti-historicism. “Art history” may at best be conceived as a history of different degrees of fidelity to art’s essential nature and the manifestations in worldly form of its absolute ideal. Art, in its real nature, never “develops”; it only goes into eclipse and returns in time, but is itself neither temporal or historical. As Behne writes:

“[Art] returns there where a great community becomes creative-vital, working its way out of a contingent, meaningless, and thus ugly mass-apparatus in order to create the peace of an image of the cosmos swinging along sure paths” (36).

In contrast to art historicism, which hypostatizes aspects of the work as “style” and situates them within period and context, Behne asserts the priority of the social order and its relation to the cosmos to that of artistic criteria. “Art,” as he writes, “is never a beginning, rather the last link in a chain…. Art is… not a goal… but rather a proof that everything else is human, definitive, and genuine” (36).

Ultimately, at the conclusion of his book, Behne pulls all the threads of his argument—from his critique of individualist art, to motifs such as his praise of glass architecture, opposition to technology and the technically accelerated pace of life, affirmation of folk art and kitsch, and evocation of a collective spiritual transformation through a renewed architecture—into a religious-existentialist climax. The ultimate source of the various negative manifestations of modernity, Behne argues, can be traced to that fear of death that most fundamentally characterizes European humanity (in this we can hear an anticipation of Heidegger’s critique of inauthenticity in Being and Time, published eight years after Behne’s book). “For the fear of death of the modern European,” Behne writes, “is perhaps the deepest primal basis of his absence of culture. In this fear is rooted his haste. In the isolation in which he lives, he sees his life as a short residence between two dark abysses” (113).

In his concluding paragraphs, Behne evokes a point of crisis and decision, which he characterizes as a choice between technology or art as the guiding orientations of European life. In a striking formulation expressing the same antithesis, he contrasts the “individualist” of technological modernity to the new artistic-spiritual community of European man who has overcome his fear of death by participation in an anonymous, spiritual art of the people. Behne calls this expressionist new man, “dividualist,” acknowledging his capacity to relinquish his sharp boundaries and dissolve into a mass gathered around a renewed, respiritualized architecture:

“The fear of death makes the European into an egoist, an individualist. He views himself as a unity…. But we are dividualists, we already were and will be, and we easily divide ourselves. Enemy of all rigidity, we surrender ourselves and build upon the great totality that may grow over generations, without even leaving behind a name for posterity, which remains our common world. In short, as dividualists we are socialists, in the most original, deepest, ultimate fraternal sense. We give way to the masses, who know no fear of death—and love!” (114).

My most favorite post to date. Must be all the years of saying what Sufis call The Invocation which begins… “Towards the One…” Thank you!

Thanks, Jim!