Linda Ellia, Our Struggle: Responding to Mein Kampf

Exhibited at Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, California, 11 February-8 June 2010

http://www.notrecombat.net/pages/en/menu.htm

In the Holy Koran, the term “people of the book” refers to non-Muslim peoples whose religions have at their center a sacred book, specifically the Christians and the Jews. While Catholicism disavowed this designation, the Jews in contrast embraced it, making it their own: with the Hebrew term “Am HaSefer,” they identified their existence and survival as a people with their holy books. A long tradition of interpretative glossing and arguing over passages, words, and even individual letters in the Torah, Talmud, and Mishnah—sometimes legalistic, othertime mystical—maintained this central focus of Jewish identity across centuries of diaspora and carried over even into modern secular Jewish culture. As late as the twentieth century, for Jewish intellectuals from Sigmund Freud and Walter Benjamin to Emmanuel Levinas and Jacques Derrida, the book still bore the trace of a sacred repository of living truth.

French artist and photographer Linda Ellia remobilizes this heritage in relation to an object that might, from the perspective of Jewish history, be considered the absolute “anti-book,” a violent antithesis of the defining books of Jews: Mein Kampf (My Struggle). the programmatic writ of Nazism that Adolf Hitler produced in prison in 1924. In 2005, when her daughter showed her a copy of the French translation of Mein Kampf, she felt overwhelmed by the need to intervene, to discharge the evil power of its script through artistic negation.

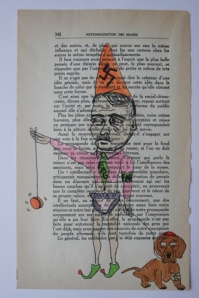

Ellia first herself worked on thirty pages, drawing, writing, painting directly upon them. Later she began reaching out to other artists and friends for their contributions, and eventually to strangers in cafés and the streets, who were solicited to offer their part in “our struggle” against all that Mein Kampf represented. Sometimes Ellia’s request provoked hostile, even racist responses; but from many, the odd request to deface a page of Mein Kampf elicited personal memory, moral reflection, and political solidarity, as well as an extraordinary diversity of artistic inventiveness. Ultimately, she received contributions to the project from seventeen countries and from both named professional artists—ranging from fine arts practitioners to cartoonists and fashion designers—and anonymous participants. In 2007, she published 600 of these interventions as the book Notre Combat, from which this exhibition in the Contemporary Jewish Museum draws 450 of the original pages.

A viewer’s first impression of the exhibit is the sheer proliferation of images resulting from Ellia’s solicitation of more and more people in the task of struggling together artistically with Hitler’s book. One rather surprising feature of the responses is that while many clearly refer to Hitler, the Holocaust, and the concentration camp, many do not. In a sense, these resist Hitler’s book by refusing to be controlled by its content or history. Many of the pages are adorned with satirical, graffiti-like, or cartoonish drawings; some are rendered purely abstract or even ornamental; several feature objects like feathers, cut paper, thread, ribbons, and other collage elements such as eyeglasses, a syringe, and a toy soldier gun and bullets.

In a fascinating juxtaposition of historical time-frames and emotional modes, one page is transformed into a 1960s Haight-Ashbury psychedelic poster, with references to the Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, and the Beatles; a tiny Yellow Submarine is pasted to the page and letters spell out the words ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE. Another selects out individual letters from Hitler’s text to spell out the words “amour” (love), “coeur” (heart), “amitié” (friendship), “paix” (peace), and “fraternité” (brotherhood). There are also three-dimensional transformations, such as a pasted-in doll and face moulded into the paper. One very striking page is covered by a Warhol-like repeated image of Anne Frank, while another pages has its text covered with Israeli stamps. In several cases, there is a meaningful interplay between the page caption of Hitler’s text and the intervention as commentary. Thus, for example, a page of Mein Kampf about the “Sterilization of Incurables” supports a collage with red and green ribbons representing a DNA strand.

This accumulation and diversity of responses are key to the implicit political meaning of the work. For Our Struggle—as an artistic figuration of the struggle against fascism and racism, which extends well beyond the historical reference of Mein Kampf—is both collective and irreducibly plural. Against the intolerant monologue of Hitler’s race paranoia, Our Struggle celebrates the plurality of responses and styles, the intermingling of professional and amateur, the named and nameless, the multiplicity of “genres” among the interventions. At least intuitively present in Ellia’s material is the underlying connection of “genre” to a set of concepts that were key to the Nazi ideological repertoire, embodying a whole logic of classification, selection, sorting, inclusion and exclusion.: type, kind, genus, gender, breed, race, One might go so far as to say that if the printed Hitlerian page represented an apotheosis of the “typological” imposition of type and stereotype—the monotonously repetitive Nazi “cliché” that should be imprinted upon the hearts of the masses—then Ellia’s contributors collectively defy this logic of type. They cut and crumple and shape and recombine the page’s texts; they contaminate its typological purity with unpredictable mélanges of pictures, collaged objects, and handwritten gestures. Partially covered, obscured, or cancelled by these works of comment and memory, the page thus becomes the medium of support for new works and new subjectivities.